Experiments with building a BPE Tokenizer

I implemented a subset of Assignment 1 from Stanford's CS 336 (Language Modeling from Scratch) involving Byte-Pair Encoding (BPE) tokenization. I expected a "cute algorithm + a couple unit tests." What I got was a surprisingly real systems problem: data structures, CPU caches, file I/O, and a lot of "why is this slower?" moments.

Check out my code here

Tokenization, BPE, and the Basic Algorithm

The lecture and assignment notes gave a great idea of why modern-day subword tokenizers are used in most language models - subword tokenization provides a decent tradeoff between a larger vocabulary size and better compression of the input byte sequence. When I first read the Byte-Pair Encoding (BPE) algorithm used by Sennrich et al. (2016), and its naïve example in the assignment notes, I was excited to try and implement the algorithm myself, without the help of Claude code and Cursor.

This is one of the benefits of being a full-time student - you are allowed to work on interesting problems with no immediate useful rewards!

The naïve implementation of BPE is actually quite simple if you think about it. You split the input corpus into pre-tokens, and then iteratively merge adjacent sets of byte-level tokens, starting from the most-frequent token pair. Every time you merge a byte-level token pair, it becomes a "sub-word" token, and it replaces all individual occurrences of the adjacent bytes with the merged token. The next maximally frequent pair of tokens is picked up, merged, and the process repeats.

- Start with a base vocabulary

- Pre-tokenize the corpus

- Repeatedly:

- Count all adjacent token pairs.

- Merge the most frequent pair into a new token.

- Update counts and repeat until you hit a target vocab size.

Simple, right? Well not quite so simple. It took me a couple of days to successfully pass all the test cases on my algorithm. I immediately tried jumping to the most "optimal" solution (thanks to years of leetcoding) and could not have guessed that the actual solution would end up involving a complex mix of data structures, optimization techniques, parallelization, and File I/O computer architecture internals. Phew! The catch is that "count all adjacent pairs, then update everything" becomes brutal once your dataset is gigabytes and your vocab target is 32K.

Experimental Setup

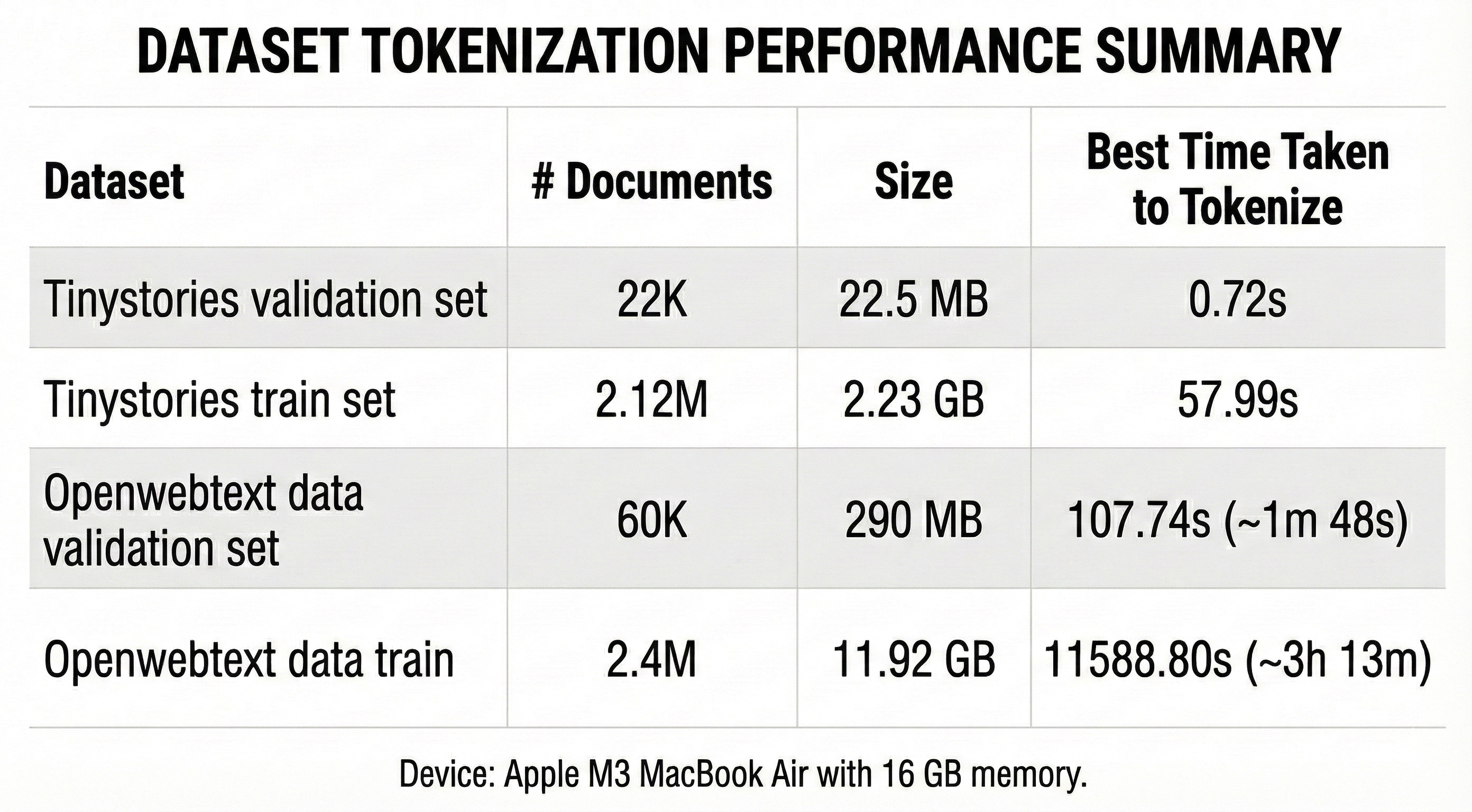

- Device: Apple M3 MacBook Air, 16GB RAM

- Datasets (size + doc delimiter counts):

- TinyStories Val: 22.5MB - 27,630 occurrences of

<|endoftext|> - TinyStories Train: 2.23GB - 2,717,699 occurrences of

<|endoftext|> - OWT Val: 290MB - 59,059 occurrences of

<|endoftext|> - OWT Train: 11.92GB - 2,399,397 occurrences of

<|endoftext|>

- TinyStories Val: 22.5MB - 27,630 occurrences of

- Vocab sizes:

- 500 (TinyStories Val)

- 10,000 (TinyStories Train)

- 32,000 (OWT Val/Train)

What counts as "# merges" in my logs?

I start from:

- 256 base byte tokens

- + special tokens (e.g.

<|endoftext|>)

Then I run:

merges = vocab_size - (256 + #specials)

That's why:

- vocab_size=500 → merges=243 (with 1 special token)

- vocab_size=10,000 → merges=9,743

- vocab_size=32,000 → merges=31,743

Implementation Journey (What Actually Mattered)

1) Correctness First: the "off-by-a-few counts" bug

BPE correctness is fragile: if your pair counts drift even slightly, the merge order changes and unit tests explode.

The bug pattern I hit was something simple, yet an edge case I completely missed: repeated pairs inside a token sequence (e.g., A B A B A B). Naively updating "before/after" counts per occurrence can double-subtract or miss boundary pairs.

💡 My fix: compute the before/after adjacent-pair multiset per affected word, then apply a diff to pair_counts (pair_counts is a dictionary with token pairs as keys and their frequency in the corpus as values). It's more expensive than a purely local update, but it's very hard to get wrong. That got me past the unit tests and gave stable merges on TinyStories Val (243 merges) and beyond.

✨ Nerd note: if you want both correctness and speed at scale, the next step is to track pair occurrences (positions), and update only local neighborhoods around each merge (no full rescans of the word). This is quite doable and I am thinking of using Cursor for a quick reimplementation. Will update here.

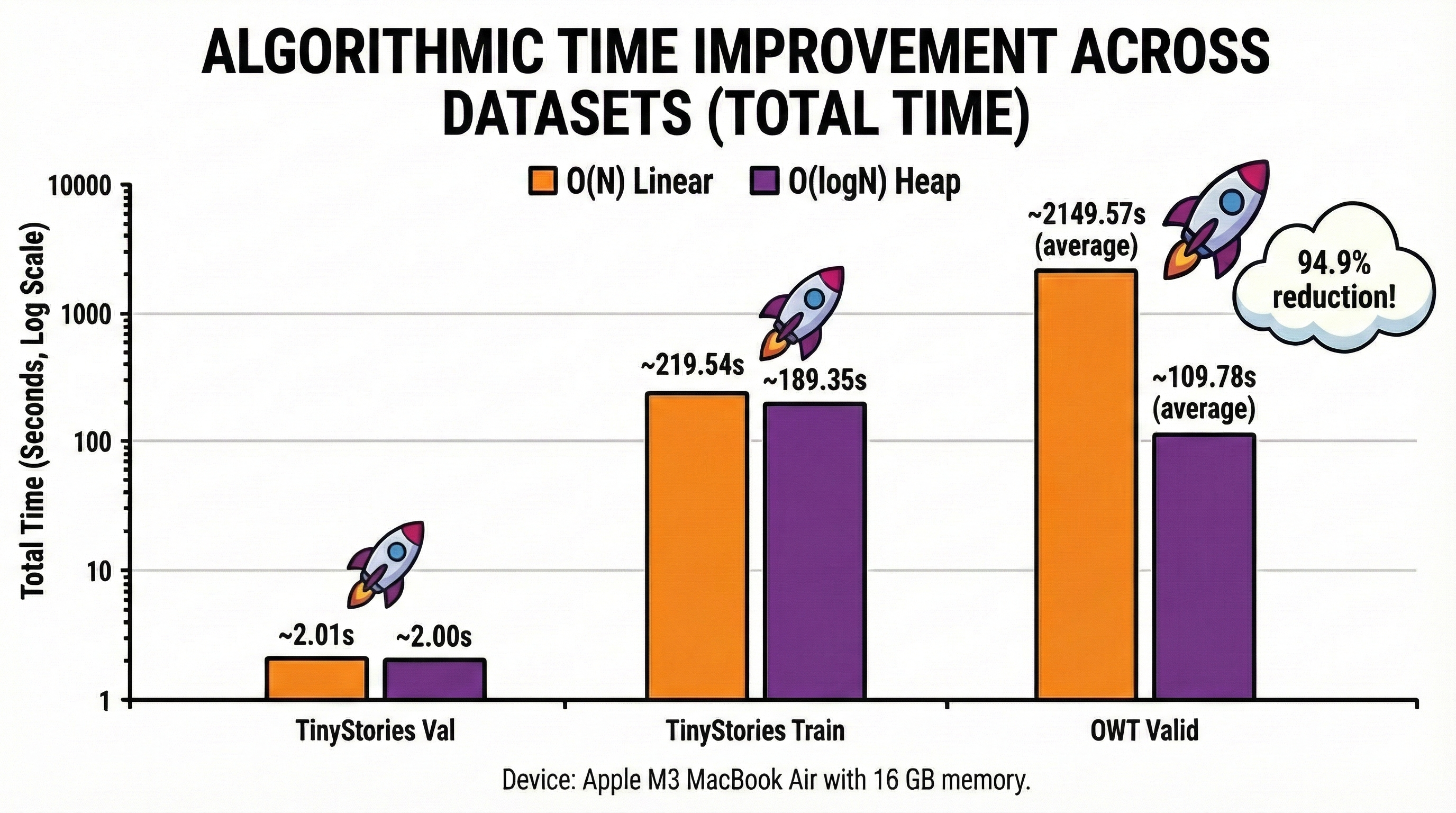

2) Max-pair selection: O(N) scan vs heap (and why "O(log N)" can lie)

I tried two strategies for selecting the most frequent pair in each iteration:

- O(N) scan of

pair_countsto find argmax. (I use the max() function in Python to perform a linear scan and choose the pair with maximum frequency) - Min-heap + lazy invalidation (I used Python 3.11 and max-heap is only introduced in Python 3.14)

Honestly speaking, when I saw the problem at hand - I have to iteratively select the maximum-frequent token pair from the corpus - I thought using a max-heap was the obvious choice. the heap invariant keeps the maximally frequent element on top. It can be accessed in O(1) time, popped in O(1) time, and any new frequencies can be pushed with O(logN) complexity where N is the average heap size.

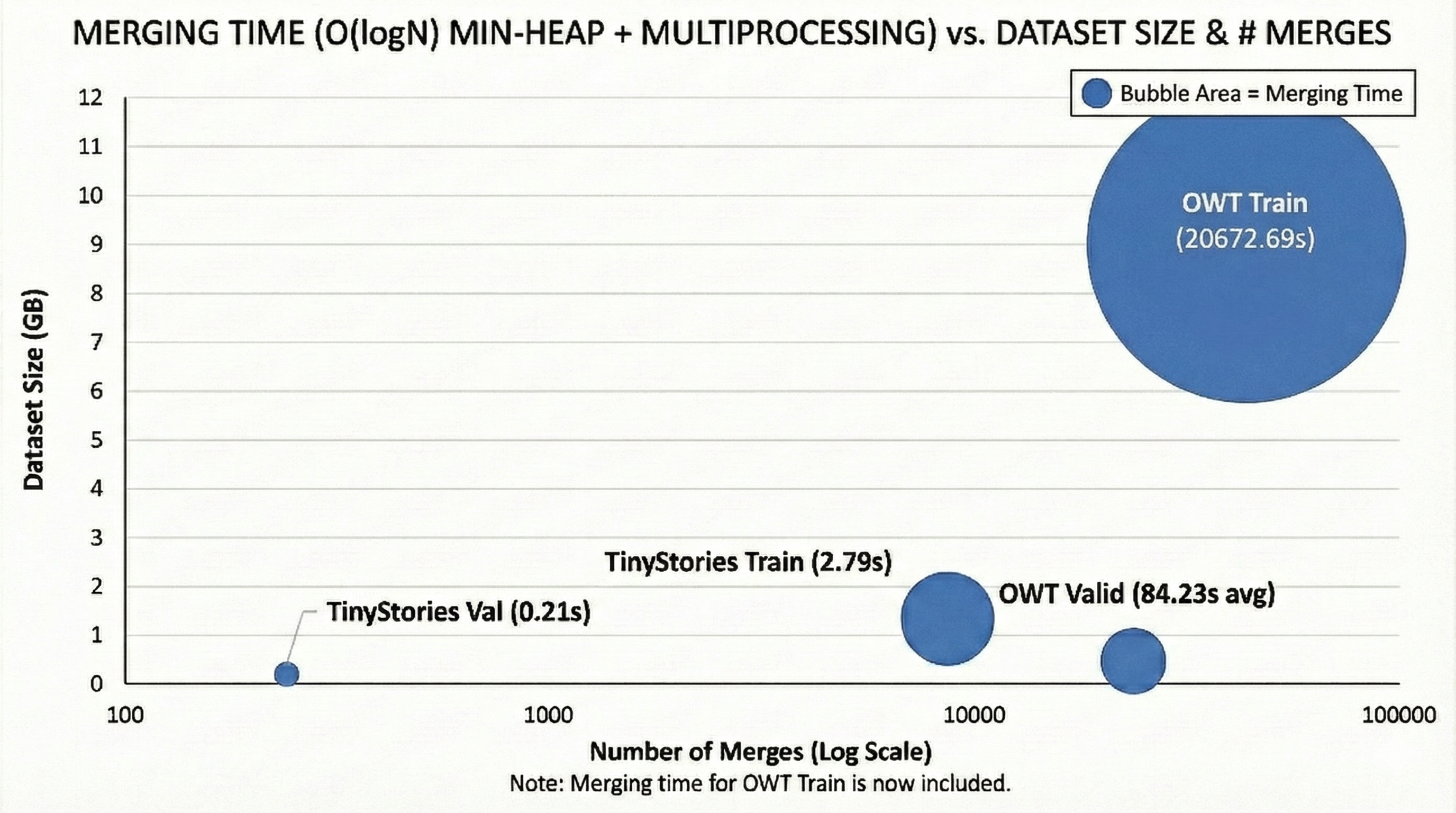

The improvement works! (and then it doesn't). For the tiny stories datasets and validation split of OWT, using a heap brings noticeable improvements in merging time. However this behavior doesn't extend to the (much larger) training set of the OWT split.

⚠️ There's a problem here ⚠️

When I merge the maximally frequent tokens, I need to update all their occurences. Thus the pair counts of some existing pairs might have to be decremented. This is handled by the pair_counts dictionary. However, the stale entries of such pair counts in the heap persist and cannot be popped feasibly. Yikes!

This means, if the count of a pair is decreased, its stale entry might still persists in the heap, even though I just pushed its updated count. It also means, the heap size will increase a lot for larger datasets because the stale entries explode.

Lazy validation is simple -

- continue popping the maximally frequent pair from heap until

- the count of the popped pair in heap matches its count in

pair_counts, meaning you have popped the latest updated entry - continue with the rest of the merging algorithm

The heap looks like an asymptotic win, but there's a systems caveat:

- If you generate too many stale heap entries,

heappop()can end up discarding huge piles of junk and become slower than the scan. - For large runs, I had to add heap compaction (periodic rebuild from

pair_counts) to prevent pathological slowdown.

The run logs show both sides of the story:

- TinyStories Train (10k vocab):

- O(N) scan → total 219.54s, merge 31.92s

- heap → total 189.35s, merge 2.87s

- (heap was a clear win here) ✅

- OWT Train (32k vocab):

- O(N) scan → total 11588.80s, merge 11306.64s

- heap

20260109_162315→ total 21018.43s, merge 20672.69s - (heap got worse due to stale-entry churn) ❌

Translation: "O(log N)" is real for argmax extraction, but your actual runtime is dominated by how much you mutate counts + how much garbage the heap accumulates.

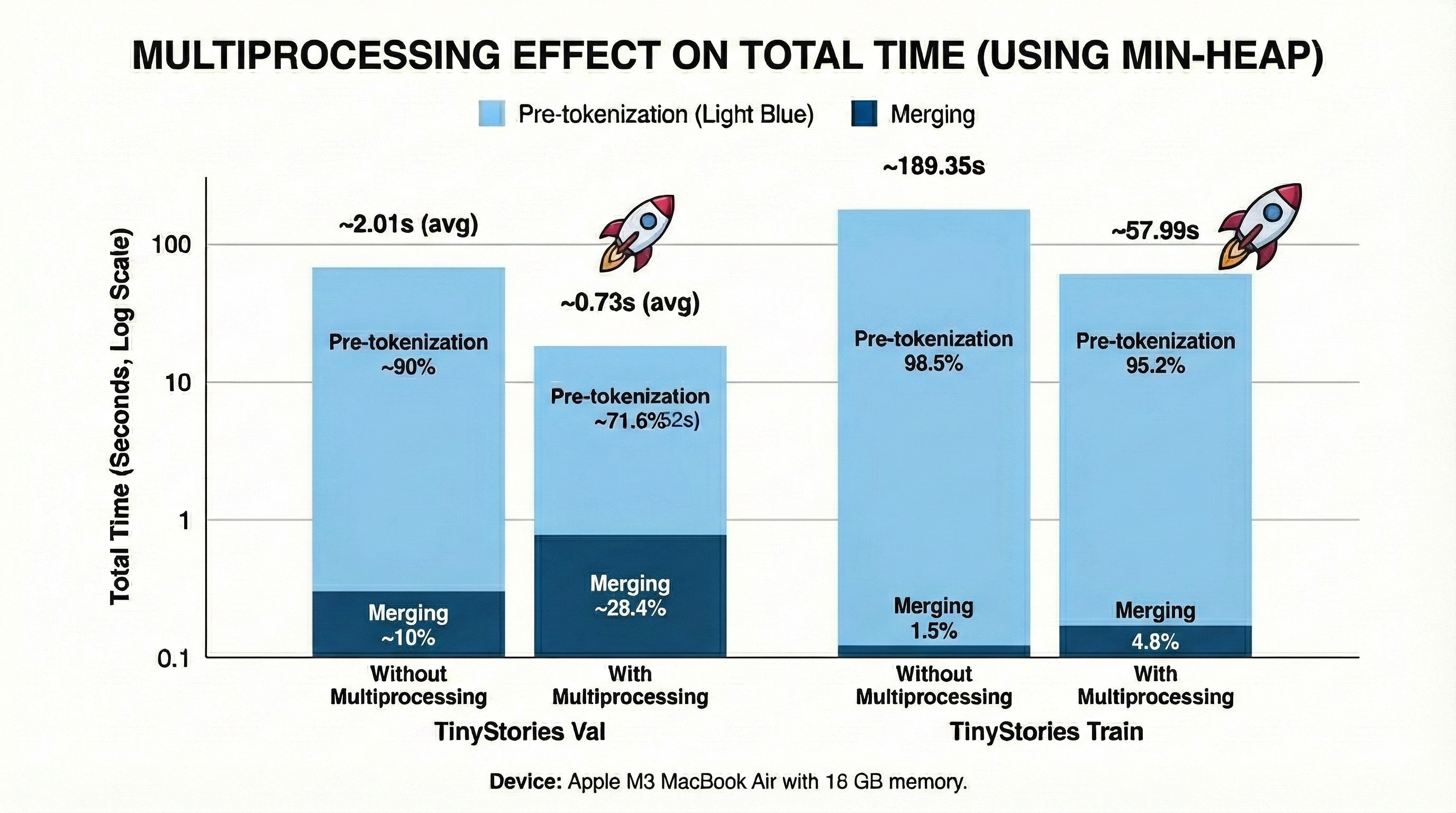

3) Parallelization: pre-tokenization is embarrassingly parallel; merging is not

Pre-tokenization is easy to parallelize because chunks can be processed independently. BPE merging is fundamentally sequential because merge (t+1) depends on the exact state after merge (t).

I parallelized pre-tokenization with multiprocessing:

- Split the file into chunk boundaries aligned on

<|endoftext|>(avoid cross-document merges). - Each worker reads its chunk and returns a

Counterof pre-token byte strings. - The parent merges counters into a global count map.

This sped up pre-tokenization substantially, but I learned the hard way that:

- spawning too many workers on a laptop can cause memory spikes (huge decoded strings + counters per worker),

- which can lead to system instability.

- my poor little Macbook crashed and rebooted multiple times initially

The fix was "boring but effective":

- fewer workers (default 4),

- smaller chunk sizes (target ~16MB),

- avoid materializing

split()lists in memory, - recycle workers (

maxtasksperchild=1).

Concrete pre-tokenization wins experimental runs:

- TinyStories Train, O(N):

- no MP → pretok 187.61s

- with MP → pretok 54.38s

- TinyStories Train, heap:

- no MP → pretok 186.48s

- with MP → pretok 55.20s

Same pretokenization code, ~3.4× faster. That's multiprocessing doing its job.

4) File caching is real (and it will gaslight your benchmarks)

I saw runs where "identical" pre-tokenization code was 2× faster on the second attempt. The reason was not magic — just OS page cache + CPU scheduling + thermals. Benchmarking on laptops requires discipline:

- alternate run order,

- discard the first warm run,

- pin your settings as much as possible.

You can see this effect in the OWT Val O(N) runs which had a runtime randomly varying between 33 and 38 minutes.

Same dataset and method; different run time. Your laptop is a noisy lab instrument.

I learned that a good representation of total tokenization time should be an average across 3-5 runs, excluding the first run. For all my experiments, I averaged the time taken for 3 runs after excluding the first cold run.

Results (Numbers)

Below are the headline results from multiple experimental runs.

TinyStories Val (22.5MB, 500 vocab, 243 merges)

Without multiprocessing:

- O(N) scan → total 2.01s (pretok 1.80s, merge 0.21s)

- heap → total 2.00s (pretok 1.81s, merge 0.19s)

With multiprocessing:

- O(N) scan → total 0.74s (pretok 0.52s, merge 0.22s)

- heap → total 0.72s (pretok 0.52s, merge 0.20s)

Takeaway: on tiny inputs, all optimizations are basically "meh"; overhead dominates. Pre-tokenization is the bottleneck. Parallelizations helps bring down pre-tokenization time!

TinyStories Train (2.23GB, 10k vocab, 9,743 merges)

Without multiprocessing:

- O(N) scan → total 219.54s (pretok 187.61s, merge 31.92s)

- heap → total 189.35s (pretok 186.48s, merge 2.87s)

With multiprocessing:

- O(N) scan → total 86.62s (pretok 54.38s, merge 32.24s)

- heap → total 57.99s (pretok 55.20s, merge 2.79s)

Takeaway: this is the "sweet spot" where heap + MP looks god-tier. Pre-tokenization is still the bottleneck. Parallelizations helps bring down pre-tokenization time and heap brings down merging time!

OWT Val (290MB, 32k vocab, 31,743 merges)

With multiprocessing (these runs are already merge-dominated):

- O(N) scan: two runs

run_1→ total 1983.55s (pretok 6.70s, merge 1976.85s)run_2→ total 2315.59s (pretok 7.48s, merge 2308.11s)

- heap: two runs

run_1→ total 107.74s (pretok 7.15s, merge 100.60s)run_2→ total 111.81s (pretok 7.20s, merge 104.61s)

Takeaway: on OWT Val, heap wins massively (merge time drops from ~2k seconds to ~100 seconds).

OWT Train (11.92GB, 32k vocab, 31,743 merges)

With multiprocessing:

- O(N) scan → total 11588.80s (pretok 282.16s, merge 11306.64s)

- heap → total 21018.43s (pretok 345.74s, merge 20672.69s)

Takeaway: this is where the "heap version should be faster" intuition died. The algorithmic story is bigger than argmax selection.

Findings (TL;DR)

Data structure optimization helps—until it doesn't

- Heap-based selection is great when the heap stays "clean."

- Lazy invalidation can accumulate stale entries and tank performance on big corpora.

- Practical fix: heap compaction when

len(heap) >> len(pair_counts).

"O(log N)" isn't the bottleneck; update cost per merge is

On OWT Train, both methods are ~98% merge time. That screams: optimize the merge update mechanics.

If you want to go full nerd, the real performance roadmap looks like:

- represent each pre-token as a mutable sequence (linked list / arrays of next pointers),

- maintain pair occurrences (pair → positions),

- update only the 2-neighborhood around each merged occurrence.

That's how you get from "hours" to "minutes" on 32k merges.

Bottlenecks shift with dataset size

- Small datasets: selection strategy matters a bit; everything is fast.

- Mid datasets: pre-tokenization becomes noticeable.

- Large datasets (OWT train): merging dominates; the main win is optimizing update cost per merge, not just argmax selection.

Multiprocessing is a win (with guardrails)

- Pre-tokenization parallelizes cleanly.

- But "max workers" is not the goal; "max throughput without memory death" is.

Longest-token artifacts are a reality check

On OWT, my longest learned tokens sometimes decode into weird byte soup (e.g., repeated "Ã/Ä" glyphs). That's not necessarily a bug: BPE operates over bytes and happily merges non-UTF8-friendly sequences if they're frequent.

Conclusion

Tokenization looks like an NLP detail until you implement it. Then it becomes a systems problem.

If I were to take this further, the next frontier is a more advanced merging implementation:

- track pair occurrences (not just "which words contain the pair") 👨🏻💻

- update only local neighborhoods around merged occurrences 😎

- avoid global rescans/diffs per merge 😩

- use doubly linked lists ⬅️ ➡️

Tokenization is fun. Tokenization is pain. Tokenization is real engineering.